|

7/13/2021 0 Comments Li Tianji. The Skill of Xingyiquan. Translated by Andrea Falk. TGL Books, 2000.The initial draft began in 1958 by Li Yukon (1885-1965) and was later completed by his son Li Tianji. This translated version was completed in 2000 by Andrea Falk of the Wu Shu Centre.

What makes this book on Xingyiquan (form and intent boxing) unique is the collaboration between martial masters (father and son) and masterful translation by an expert practitioner. This makes for a comprehensive and we'll laid out manual of this relatively underrepresented art (compared to Taji Quan and Bagua Chang which together represent what many call the "big three" internal arts). Included alongside the detailed technical aspects of the art there is background theory, stance training for health, and translations of classic texts (which are printed out in Chinese for those interested). Highly recommend for those interested in Xingyiquan and Traditional Chinese Martial Arts (TCM) in general. Reviewed by Brian Gibson Brian Gibson is a professional artist whose show Ink and Brush exhibited a collection of his work from his tour in Japan. His martial arts experience includes Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu (Seitokai), Shindo Muso Ryu Jodo, is the lead instructor at Denton Tai Chi, Denton, Texas.

0 Comments

Mishima, Yukio. The Way of the Samurai: Yukio Mishima on Hagakure in Modern Life. Translated by Kathryn Sparling. New York: Basic Books, 1977.THIS WORK IS CURRENTLY OUT OF PRINT (OOP) AND DIFFICULT TO FIND.A translation of Mishima’s Hagakure Nyūmon. Yukio Mishima, author, artist, and failed leader of a military coup in 1970, collected his commentary on Hagakure in a series of essays that kept Hagakure and himself in notoriety well into the twentieth century. In these, Mishima revealed a complicated and often incomplete intellectual relationship with Hagakure, perhaps in part because of his own limited reading of the work. Especially related to action and death, Mishima easily connected his fatalist appreciation to Yamamoto’s works. In other places, however, Mishima expended considerable energy to construct weak arguments and in other places outright misinterpreted the material to justify his world view’s supposed alignment with Hagakure. As an essayist, Mishima demonstrated minimal accomplishment in depth of analysis. His theses often lacked evidence and his arguments lacked structure. Reading through his thoughts, it is as if he found a brief glimpse of insight and fought in vain to construct a path to it, winding through philosophical traditions hundreds of years and thousands of miles removed from Yamamoto Tsunetomo. The history of Hagakure began nearly two hundred years before The Pacific War, but it's this conflict that brought it to Mishima’s attention. Undoubtedly, the intense emotions surrounding this conflict informed his appreciation of it. Burning onto the literary scene from relative obscurity in the two hundred years before, it received wide-sweeping interpretation and acceptance as a text to elevate the people of Japan to the image of the idealized samurai. The work grew from being a key text of a relatively isolated domain to a nationalized document. It served to reduce the ego to nothingness to better face death and glorify self-sacrifice for the Empire. In this, young men marching to war found comfort and those at home found it “...[S]ocially obligatory reading...”[1] as Yukio Mishima described his memories of Hagakure during the war. In few places can readers observe better the role of Hagakure as literature to drive nationalism than in the writings of kamikaze pilots. Yukio Mishima described this connection in his essay “How to Read Hagakure.” According to Mishima, “...the spirit of those young men [Kamikaze] who for the sake of their country hurles themselves to certain death is closest in the long history of Japan to the clear ideal of action and death offered in Hagakure...”[2] Mishima’s assessment found a supporting historical account in at least one instance--the life and death of Iwabe Keiziroo, a kamikaze pilot, as described by his acquaintance Honda Toshiaki. Through his meeting with Iwabe, Honda discovered Hagakure and witnessed the influence of the work-- though only a fraction of it--as the textbook of the “Nabeshima's samurai's way” and a model of behavior for young men thrust into cataclysmic violence of The Pacific War.[3] A particularly notable memory Honda shared about Iwabe’s lessons from Hagakure appeared in his recitation of the opening lines: “[Iwabe] often told about the text of Hagakure. ‘A samurai's way is understanding dying. When there are two ways, the samurai should choose to die early. So and so.’”[4] It gave teenage boys destined to pilot their aircraft to the death a world view that encouraged actions without the thought of consequence beyond death. In Honda’s words, Hagakure gave the kamikaze “the frightful life of not considering a survival from the start.”[5] Iwabe carried out his last mission on August 9, 1945. With the surrender of Imperial Japan on August 15, 1945 (less than a week after Iwabe’s fateful flight) the public opinion of Hagakure quickly changed. No longer did it hold a critical role in the cultural psyche but became something associated with painful memories or personal loss and national defeat. What’s more, with the American occupation, the text itself became verboten. As Kathryn Sparling, translator of a collection of Mishima’s essays, described it, “After the war, Hagakure was quickly abandoned as dangerous and subversive. Many copies were destroyed so they would not meet the eyes of the Occupation authorities.”[6] All but forgotten, the work would have been relegated to memory were it not for Mishima’s interest and writings. Throughout his essays, also available in English, Mishima composed several passages where Yamamoto’s voice--incorrectly so--seems to serve no other function than to add gravity to Mishima’s own arguments through a dizzying and suspect use of sources to support a tenuous argument.[7] In an attempt to support his own ideas on health and fitness, he added Yamamoto’s notes and explained, “[Yamamoto] says, ‘If only you take good care of your health, eventually you will fulfill your greatest desire and serve your daimyo well.’”[8] Mishima continued to comment on how this is uncharacteristic of Yamamoto’s nihilism, and explained the matter as one of developing individual resolution towards death. In doing so, however, he ignored the clear language of taking care of self to better serve another used by Yamamoto--selflessness and service being cornerstones of Yamamoto’s philosophy as evident throughout the work. This reduced emphasis on selflessness and service appeared throughout Mishima’s essays. Nowhere else did Mishima draw such a strong contrast against Yamamoto than in his own sense of exceptionalism. According to Sparling’s analysis, “Always, [Mishima’s] emphasis is on the individual, whose ultimate goal is self-cultivation rather than contribution to his immediate environment or to society.”[9] Here, Mishima failed to connect with Yamamoto, despite his best efforts to muster thousands of years of philosophy across several cultures. At the core of his philosophies, perhaps in part because of his Confucian education, Yamamoto frequently referenced the importance of service--to being a useful retainer that contributed to the success of his lord and by extension domain. Even when compared to the use of Hagakure by Kamikaze like Iwabe, Mishima’s assessment missed the mark. Though death played a role in these interpretations, it did not serve as the focus. It served, rather, as an ends. The means to that end were selfless service, albeit selfless service that often ended in great sacrifice and death in the name of the glory of the Emperor. Ironically, it is here that he built his identity within the words of Hagakure and, in doing so, constructed a self-psyche that could only be defined by those things that were exceptional and different. “If there is still a reason for reading [Hagakure], I can only guess that it is for considerations completely opposite to those during the war.”[10] Despite this observation, Mishima revealed his own fascination with death in his essays and in doing so ultimately demonstrated his thinking not far removed from wartime readers, except perhaps in his own omission of selflessness and service. In other places, Mishima’s logic fell short of constructing confident connections between ideas and strayed into areas of tenuous arguments to justify his world view. Often, this is done to support his own extremist or nonconforming conclusions. For example, in his essay “Hagakure and I,” Mishima argued that “[Yamamoto] tries to be faithful to the Way of the Samurai by vigorously rejecting Shinto Taboos. Here the traditional Japanese idea of defilement is completely trampled underfoot before the desire for violent action.”[11] Mishima then repeated the passage with this line and, in doing so, exposes his misunderstanding, highlighted by the opening line, “Although they say the gods dislike contamination, I have my own opinion on the subject. I never neglect my daily worship. Even when I get spattered with blood on the battlefield, or stumble over corpses underfoot as I fight, I believe in the effectiveness of praying to the gods for military success and long life...”[12] Mishima’s limited understanding of Japanese intellectualism remained consistent throughout his essays. Frequently, he seemed to either not understand or completely disregard the critical behavior and philosophies found in both Hagakure. This appeared notably in his essay “Hagakure and I” where he argued that Hagakure had to be his guiding book because, like him, it stood outside the pale of mid-twentieth century Japanese acceptance: “What is more, it must be a book banned by contemporary society.”[13] Mishima drew this connection as he sought a kindred spirit in Yamamoto, seeing himself too as an anachronism of a man meant to live in days long gone. Unfortunately, in this Mishima either failed to recognize--or outrightly ignored--the issue that his artistic pursuits were exactly the livelihood that Yamamoto spoke out against in his time. Mishima wrote elsewhere in the same essay that it is because of Hagakure that “In fact, to tell the truth, my firm insistence on the ‘Combined Way of the Scholar and the Warrior’ I owe to the influence of Hagakure,” because it is through this that art is no long art for art’s sake, but a struggle of life and death.[14] Here, he returned to his personal fascination with death. Examined carefully, readers discover that Hagakure is less about death than Mishima ascribed to it. This focus developed in his essays as Mishima made a great effort to find his voice in others-- to justify his fatalistic philosophies with echoes from bygone eras--and tenuously so at best. Yamamoto’s words seemed more frequently to describe the service and dedication of a man struggling to continue to uphold his duty despite his inability to follow his master. These values stood in stark contrast to Mishima’s self-exceptionalism. Despite this, Mishima’s essays and actions, and their influence on early translators, laid at his feet the responsibility for the transmission of the Hagakure cult of death and emphasis on extremism and violence in the English Hagakure tradition, as his influence through his art and his renowned death helped to introduce Hagakure to English readers. Notes

[1] Mishima, “Hagakure and I,” The Way of the Samurai: Yukio Mishima on Hagakure in Modern Life, trans. Kathryn Sparling (New York: Basic Books, 1977), 4. [2] Mishima, “How to Read Hagakure,” The Way of the Samurai: Yukio Mishima on Hagakure in Modern Life, trans. Kathryn Sparling (New York: Basic Books, 1977), 101. [3] Honda Toshiaki. “I Want to Become the Hagakure.” A Classmate’s War Experience. Warbirds-JP. March 16, 2003. http://www.warbirds.jp/senri/19english/dooki/01/index.htm. [4] Honda. [5] Honda. [6] Kathryn Sparling, “Translator’s Note,” The Way of the Samurai (New York: Basic Books, 1977), xiii. [7] Other scholars’ work established and examined Mishima’s questionable skills as an essayist. In his work Japanese Confucianism: A Cultural History, Paramore examined other instances of Mishima’s superficial--or at times outright incorrect--understanding of works, especially related to his failed coup in 1970. For more, see Kiri Paramore, Japanese Confucianism: A Cultural History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017). [8] Mishima, “Hagakure and I,” 93. [9] Kathryn Sparling, ix. [10] Mishima, “Hagakure and I,” 99. [11] Mishima, “Hagakure and I,” 89. [12] Mishima, “Hagakure and I,” 89. Emphasis added by author. [13] Mishima, “Hagakure and I,” 6. [14] Mishima, “Hagakure and I,” 10. YAMAMOTO TSUNETOMO. HAGAKURE: THE CODE OF THE SAMURAI - THE MANGA EDITION. TRANSLATED BY WILLIAM SCOTT WILSON. ADAPTED BY SEAN MICHAEL WILSON. ILLUSTRATED BY CHIE KUTSUWADA. TOKYO: KODANSHA, 2011."After reading books or the like, it is best to burn them or throw them away." Yamamoto Tsunetomo, Hagakure.

The abstract concepts of philosophy are often difficult to communicate to audiences, if for no other reason because of the ineffectiveness of language. Foreign cultures, translated languages, and philosophies far removed in time further complicate matters. Using a visual component, however, can aid readers in understanding these concepts. Sean Michael Wilson's manga adaptation of William Scott Wilson's translation of Yamamoto Tsunetomo's Hagakure attempts to present to readers a visually appealing interpretation of the central concepts found in the two-hundred-year-old treatise on samurai behavior. Though useful as an introduction to this field of study, the selection of certain items over others, presents this the source material only in partial and limits readers understanding of the entire context--historical, cultural, and philosophical--of the work. Because of the intertwined relationship of the three authors, it is necessary to begin with a few words on each. The original progenitor of the Hagakure is Yamamoto Tsunetomo, an eighteenth- century samurai and former retainer of the Nabeshima. When his feudal lord, Nabeshima Mitsushige, died in 1700, Yamamoto was unable to follow his lord in death through suicide due to both the proclamations of the Tokugawa Bakufu and Nabeshima Mitsushige's own wishes. As an alternative, Yamamoto entered the Zen priesthood. In 1710, he received visits from a young samurai, Tashiro Tsuramoto, who later recorded Yamamoto's words of wisdom in what became the Hagakure. Yamamoto shared his concerns for and observations of samurai behavior during the eighteenth century. According to his assessments, and much to his vexation, samurai of his day were less interested in serving out their traditional roles as loyal retainers from the class of military elite and more concerned with ostentatious extravagances. William Scott Wilson is one of the most influential translators of the Hagakure. Wilson found his way to the Hagakure from his interest in the works of Mishima Yukio, including his series of essays Hagakure Nyūmon. His original translation of the work, published by Kodansha with assistance of a grant from the Japan Foundation, appeared in 1979. His original translation possessed a selection of the original transcriptions of the Hagakure, approximately three hundred of the original thirteen hundred--Japanese editions often exclude a number. To his credit, William S. Wilson did include more selections of the original Japanese in his edition, though not the entire work. The final author in the triumvirate is Sean Michael Wilson. Modern readers will note Wilson for his efforts in producing graphic novels, especially of important works in literature including Nitobe Izano’s Bushido, Miyamoto Musashi’s Book of Five Rings, Issai Chozanshi’s Demon’s Sermon on the Martial Arts, and Laozi’s Dao De Jing. To complete his works, Wilson works in conjunction with British, Chinese, Korean, and Japanese artists. He also lectures on topics related to manga throughout the United States and Great Britain. This interpretation of the Hagakure presents Yamamoto's advice in a series of anecdotes told during the meetings between Yamamoto and Tashiro. Each of five chapters covers one specific topic from the Hagakure: "The Way of the Samurai," "Loyalty," Revenge," "Kaishaku and Seppuku," and "Sincerity." Each chapter depicts a distinct meeting between Yamamoto and Tashiro, wherein Yamamoto recalls stories from the bygone eras of ideal (according to Yamamoto) samurai behavior to illustrate his points. This arrangement provides a level of structure absent from the original edition produced as recorded and not organized. The manga edition of the Hagakure highlights a few essential lessons that communicate central concepts in behavior expected of Nabeshima samurai. These include humility and selflessness, confidence and resolution, and the importance of proper behavior within social contexts (e.g., using proper manners and not bullying others). What is difficult to extract from the work, especially the manga edition, is that much of the philosophical underpinnings highlighted there echo closely the ideals of Confucianism Yamamoto received in his education. Nevertheless, though a work inspired by centuries old Chinese civil philosophy and originally composed nearly three hundred years ago for a Japanese audience, these lessons apply just as well to modern readers from a variety of backgrounds. This work, however, is a broad overview of philosophy as interpreted by Yamamoto Tsunetomo. Though in the manga many breeches of etiquette were solved with the quick cut of the sword, such problem resolutions are impossible in today's world. This, perhaps, makes some elements of samurai ethics (as recounted in this manga) more difficult to maintain. As a result, without immediate consequences, or the ability to enforce immediate consequences, it requires a greater amount and quality of self-discipline and personal courage to be an upstanding person in today's society. This is critical for readers to bear in mind. 2/19/2021 0 Comments BUDO PERSPECTIVESBudo perspectives: Volume 1. Edited by alexander Bennett. AucklaNd, New ZealAnd: Kendo World Publications, Ltd, 2005.This collection of essays born from the 2003 international symposium “The Direction of Japanese Budō in the 21st Century: Past, Present, and Future,” meets a momentous need of expanding the studies of Japanese martial arts into critical scholarship. Divided into four sections, the essays tease out philosophical, cultural, educational and pedagogical, and international theses that both examine historical significance as well as evaluate the contemporary factors intertwining Budō and modern society demonstrating that in a world where men and women no longer walk the streets of the globe with swords, Budō holds a place of importance in modern, global society. The presenters come to these studies as both scholars and martial artist giving their works both rigorous scholarship as well as keen insights as practitioners of various arts.

The most widely discussed arts include judo, kendo, karate, and aikido because of both the historical gravity of the leaders of these arts but also the wide-spread practice of these arts on a global scale. Perhaps not as widely practiced, kyudo also receives significant attention because of the near-death, rebirth, then early introduction to an international audience of the art and its since intertwining with Zen. Rich with thorough scholarship, this collection of papers opens the door for further detailed analysis of Japanese martial arts in the English language. 2/19/2021 0 Comments In the dojoLowry, Dave. In the Dojo: A Guide to the Rituals and Etiquette of the Japanese Martial Arts. Boston: Weatherhill, 2006.Titled as a guide to ritual and etiquette, this work also includes elements of history and anecdotes from the life of the author. It serves as a reasonable, general overview of goings on in a dojo. Divided into 13 chapters, Lowry covers topics ranging from the arrangement of the dojo and the elements of the shrine; the roles, behaviors, and responsibilities of visitors, students, and teachers; actions in daily practice and yearly events; and uniforms and equipment. In his efforts to be broad and far reaching, the chapters themselves provide readers a cursory glance into these topics from a variety of angles, from the eyes of students of a traditional art like those of many koryu to a more modern art like Judo or Aikido.

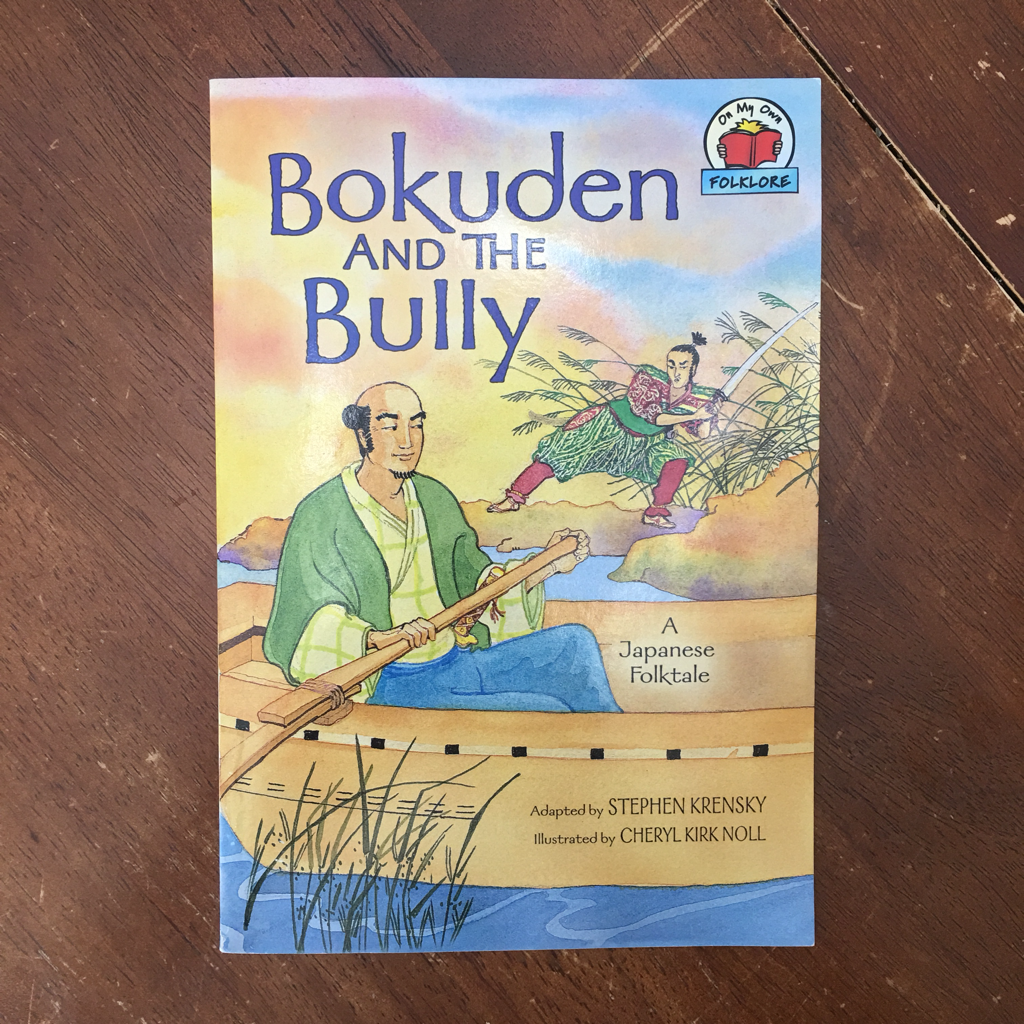

. Largely, Lowry draws from his own experiences as dramatically narrated anecdotes cover the pages quite frequently. On the occasions Lowry references other sources, such as historical records from organizations such as the Kodokan, he disappointingly does not include citations, footnotes, or a bibliography. This shortcoming limits the usefulness of this work beyond a cursory overview from only the author’s perspective. . For readers who have spent a length of time in a Japanese budo, Lowry’s In the Dojo will largely confirm what they already learned with a few opportunities for contemplation. This work serves best as an introductory work for students new to training in Japanese martial arts. The wide ranging topics he addresses will provide signposts to help neophytes navigate the myriad of strange, new, and sometimes uncomfortable experiences of starting any budo. Perhaps most important, especially for this audience, in one form or another Lowry repeatedly notes that his experience may differ and when questions arise, students should always defer to their sensei. 8/30/2019 0 Comments Bokuden and the BullyKrensky, Stephen. Illus. Noll, Cheryl Kirk. Bokuden and the Bully. Minneapolis: Millbrook Press, 2009. 48 pages. |

REVIEWSBudo Book Review strives to provide thoughtful, in-depth reviews of works of interest to martial artists from a variety of backgroubds. Archives

July 2021

CategoriesAll Alexander Bennett Andrea Falk Antony Cummins Ashigaru Brian Gibson Budo Bushido Children's Literature China Chinese Martial Arts Dave Lowry Dojo Etiquette Folk Tales Hagakure History History Press Kashima Shin Ryu Kathryn Sparling Kendo World Literature Li Tianji Li Yukon Mishima Yukio Philosophy Samurai Taiqi Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto Ryu Tsukahara Bokuden Volume 1 Number 1 August 2019 Volume 2 Number 1 March 2021 Weatherhill William Scott Wilson Women Wo Shu Yamamoto Tsunetomo Yoshie Minami |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed