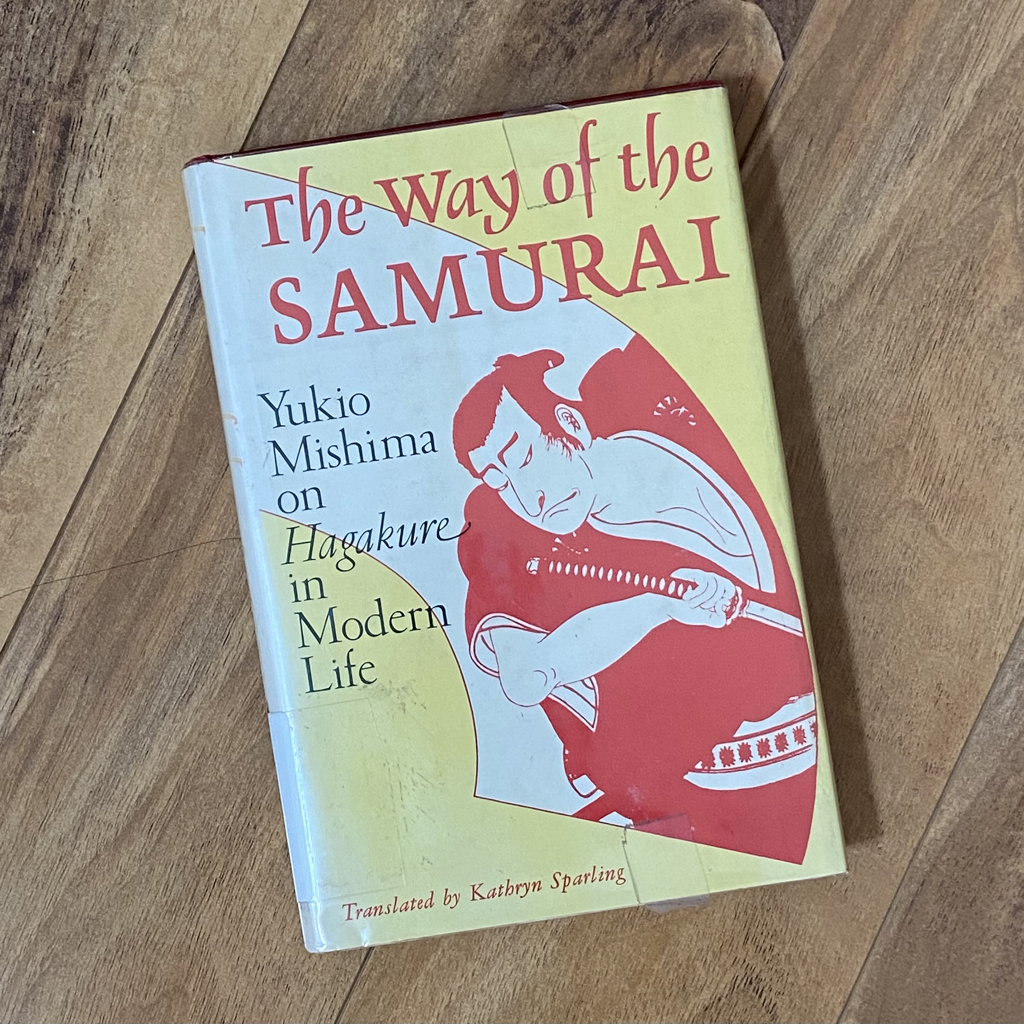

Mishima, Yukio. The Way of the Samurai: Yukio Mishima on Hagakure in Modern Life. Translated by Kathryn Sparling. New York: Basic Books, 1977.THIS WORK IS CURRENTLY OUT OF PRINT (OOP) AND DIFFICULT TO FIND.A translation of Mishima’s Hagakure Nyūmon. Yukio Mishima, author, artist, and failed leader of a military coup in 1970, collected his commentary on Hagakure in a series of essays that kept Hagakure and himself in notoriety well into the twentieth century. In these, Mishima revealed a complicated and often incomplete intellectual relationship with Hagakure, perhaps in part because of his own limited reading of the work. Especially related to action and death, Mishima easily connected his fatalist appreciation to Yamamoto’s works. In other places, however, Mishima expended considerable energy to construct weak arguments and in other places outright misinterpreted the material to justify his world view’s supposed alignment with Hagakure. As an essayist, Mishima demonstrated minimal accomplishment in depth of analysis. His theses often lacked evidence and his arguments lacked structure. Reading through his thoughts, it is as if he found a brief glimpse of insight and fought in vain to construct a path to it, winding through philosophical traditions hundreds of years and thousands of miles removed from Yamamoto Tsunetomo. The history of Hagakure began nearly two hundred years before The Pacific War, but it's this conflict that brought it to Mishima’s attention. Undoubtedly, the intense emotions surrounding this conflict informed his appreciation of it. Burning onto the literary scene from relative obscurity in the two hundred years before, it received wide-sweeping interpretation and acceptance as a text to elevate the people of Japan to the image of the idealized samurai. The work grew from being a key text of a relatively isolated domain to a nationalized document. It served to reduce the ego to nothingness to better face death and glorify self-sacrifice for the Empire. In this, young men marching to war found comfort and those at home found it “...[S]ocially obligatory reading...”[1] as Yukio Mishima described his memories of Hagakure during the war. In few places can readers observe better the role of Hagakure as literature to drive nationalism than in the writings of kamikaze pilots. Yukio Mishima described this connection in his essay “How to Read Hagakure.” According to Mishima, “...the spirit of those young men [Kamikaze] who for the sake of their country hurles themselves to certain death is closest in the long history of Japan to the clear ideal of action and death offered in Hagakure...”[2] Mishima’s assessment found a supporting historical account in at least one instance--the life and death of Iwabe Keiziroo, a kamikaze pilot, as described by his acquaintance Honda Toshiaki. Through his meeting with Iwabe, Honda discovered Hagakure and witnessed the influence of the work-- though only a fraction of it--as the textbook of the “Nabeshima's samurai's way” and a model of behavior for young men thrust into cataclysmic violence of The Pacific War.[3] A particularly notable memory Honda shared about Iwabe’s lessons from Hagakure appeared in his recitation of the opening lines: “[Iwabe] often told about the text of Hagakure. ‘A samurai's way is understanding dying. When there are two ways, the samurai should choose to die early. So and so.’”[4] It gave teenage boys destined to pilot their aircraft to the death a world view that encouraged actions without the thought of consequence beyond death. In Honda’s words, Hagakure gave the kamikaze “the frightful life of not considering a survival from the start.”[5] Iwabe carried out his last mission on August 9, 1945. With the surrender of Imperial Japan on August 15, 1945 (less than a week after Iwabe’s fateful flight) the public opinion of Hagakure quickly changed. No longer did it hold a critical role in the cultural psyche but became something associated with painful memories or personal loss and national defeat. What’s more, with the American occupation, the text itself became verboten. As Kathryn Sparling, translator of a collection of Mishima’s essays, described it, “After the war, Hagakure was quickly abandoned as dangerous and subversive. Many copies were destroyed so they would not meet the eyes of the Occupation authorities.”[6] All but forgotten, the work would have been relegated to memory were it not for Mishima’s interest and writings. Throughout his essays, also available in English, Mishima composed several passages where Yamamoto’s voice--incorrectly so--seems to serve no other function than to add gravity to Mishima’s own arguments through a dizzying and suspect use of sources to support a tenuous argument.[7] In an attempt to support his own ideas on health and fitness, he added Yamamoto’s notes and explained, “[Yamamoto] says, ‘If only you take good care of your health, eventually you will fulfill your greatest desire and serve your daimyo well.’”[8] Mishima continued to comment on how this is uncharacteristic of Yamamoto’s nihilism, and explained the matter as one of developing individual resolution towards death. In doing so, however, he ignored the clear language of taking care of self to better serve another used by Yamamoto--selflessness and service being cornerstones of Yamamoto’s philosophy as evident throughout the work. This reduced emphasis on selflessness and service appeared throughout Mishima’s essays. Nowhere else did Mishima draw such a strong contrast against Yamamoto than in his own sense of exceptionalism. According to Sparling’s analysis, “Always, [Mishima’s] emphasis is on the individual, whose ultimate goal is self-cultivation rather than contribution to his immediate environment or to society.”[9] Here, Mishima failed to connect with Yamamoto, despite his best efforts to muster thousands of years of philosophy across several cultures. At the core of his philosophies, perhaps in part because of his Confucian education, Yamamoto frequently referenced the importance of service--to being a useful retainer that contributed to the success of his lord and by extension domain. Even when compared to the use of Hagakure by Kamikaze like Iwabe, Mishima’s assessment missed the mark. Though death played a role in these interpretations, it did not serve as the focus. It served, rather, as an ends. The means to that end were selfless service, albeit selfless service that often ended in great sacrifice and death in the name of the glory of the Emperor. Ironically, it is here that he built his identity within the words of Hagakure and, in doing so, constructed a self-psyche that could only be defined by those things that were exceptional and different. “If there is still a reason for reading [Hagakure], I can only guess that it is for considerations completely opposite to those during the war.”[10] Despite this observation, Mishima revealed his own fascination with death in his essays and in doing so ultimately demonstrated his thinking not far removed from wartime readers, except perhaps in his own omission of selflessness and service. In other places, Mishima’s logic fell short of constructing confident connections between ideas and strayed into areas of tenuous arguments to justify his world view. Often, this is done to support his own extremist or nonconforming conclusions. For example, in his essay “Hagakure and I,” Mishima argued that “[Yamamoto] tries to be faithful to the Way of the Samurai by vigorously rejecting Shinto Taboos. Here the traditional Japanese idea of defilement is completely trampled underfoot before the desire for violent action.”[11] Mishima then repeated the passage with this line and, in doing so, exposes his misunderstanding, highlighted by the opening line, “Although they say the gods dislike contamination, I have my own opinion on the subject. I never neglect my daily worship. Even when I get spattered with blood on the battlefield, or stumble over corpses underfoot as I fight, I believe in the effectiveness of praying to the gods for military success and long life...”[12] Mishima’s limited understanding of Japanese intellectualism remained consistent throughout his essays. Frequently, he seemed to either not understand or completely disregard the critical behavior and philosophies found in both Hagakure. This appeared notably in his essay “Hagakure and I” where he argued that Hagakure had to be his guiding book because, like him, it stood outside the pale of mid-twentieth century Japanese acceptance: “What is more, it must be a book banned by contemporary society.”[13] Mishima drew this connection as he sought a kindred spirit in Yamamoto, seeing himself too as an anachronism of a man meant to live in days long gone. Unfortunately, in this Mishima either failed to recognize--or outrightly ignored--the issue that his artistic pursuits were exactly the livelihood that Yamamoto spoke out against in his time. Mishima wrote elsewhere in the same essay that it is because of Hagakure that “In fact, to tell the truth, my firm insistence on the ‘Combined Way of the Scholar and the Warrior’ I owe to the influence of Hagakure,” because it is through this that art is no long art for art’s sake, but a struggle of life and death.[14] Here, he returned to his personal fascination with death. Examined carefully, readers discover that Hagakure is less about death than Mishima ascribed to it. This focus developed in his essays as Mishima made a great effort to find his voice in others-- to justify his fatalistic philosophies with echoes from bygone eras--and tenuously so at best. Yamamoto’s words seemed more frequently to describe the service and dedication of a man struggling to continue to uphold his duty despite his inability to follow his master. These values stood in stark contrast to Mishima’s self-exceptionalism. Despite this, Mishima’s essays and actions, and their influence on early translators, laid at his feet the responsibility for the transmission of the Hagakure cult of death and emphasis on extremism and violence in the English Hagakure tradition, as his influence through his art and his renowned death helped to introduce Hagakure to English readers. Notes

[1] Mishima, “Hagakure and I,” The Way of the Samurai: Yukio Mishima on Hagakure in Modern Life, trans. Kathryn Sparling (New York: Basic Books, 1977), 4. [2] Mishima, “How to Read Hagakure,” The Way of the Samurai: Yukio Mishima on Hagakure in Modern Life, trans. Kathryn Sparling (New York: Basic Books, 1977), 101. [3] Honda Toshiaki. “I Want to Become the Hagakure.” A Classmate’s War Experience. Warbirds-JP. March 16, 2003. http://www.warbirds.jp/senri/19english/dooki/01/index.htm. [4] Honda. [5] Honda. [6] Kathryn Sparling, “Translator’s Note,” The Way of the Samurai (New York: Basic Books, 1977), xiii. [7] Other scholars’ work established and examined Mishima’s questionable skills as an essayist. In his work Japanese Confucianism: A Cultural History, Paramore examined other instances of Mishima’s superficial--or at times outright incorrect--understanding of works, especially related to his failed coup in 1970. For more, see Kiri Paramore, Japanese Confucianism: A Cultural History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017). [8] Mishima, “Hagakure and I,” 93. [9] Kathryn Sparling, ix. [10] Mishima, “Hagakure and I,” 99. [11] Mishima, “Hagakure and I,” 89. [12] Mishima, “Hagakure and I,” 89. Emphasis added by author. [13] Mishima, “Hagakure and I,” 6. [14] Mishima, “Hagakure and I,” 10.

0 Comments

|

REVIEWSBudo Book Review strives to provide thoughtful, in-depth reviews of works of interest to martial artists from a variety of backgroubds. Archives

July 2021

CategoriesAll Alexander Bennett Andrea Falk Antony Cummins Ashigaru Brian Gibson Budo Bushido Children's Literature China Chinese Martial Arts Dave Lowry Dojo Etiquette Folk Tales Hagakure History History Press Kashima Shin Ryu Kathryn Sparling Kendo World Literature Li Tianji Li Yukon Mishima Yukio Philosophy Samurai Taiqi Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto Ryu Tsukahara Bokuden Volume 1 Number 1 August 2019 Volume 2 Number 1 March 2021 Weatherhill William Scott Wilson Women Wo Shu Yamamoto Tsunetomo Yoshie Minami |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed